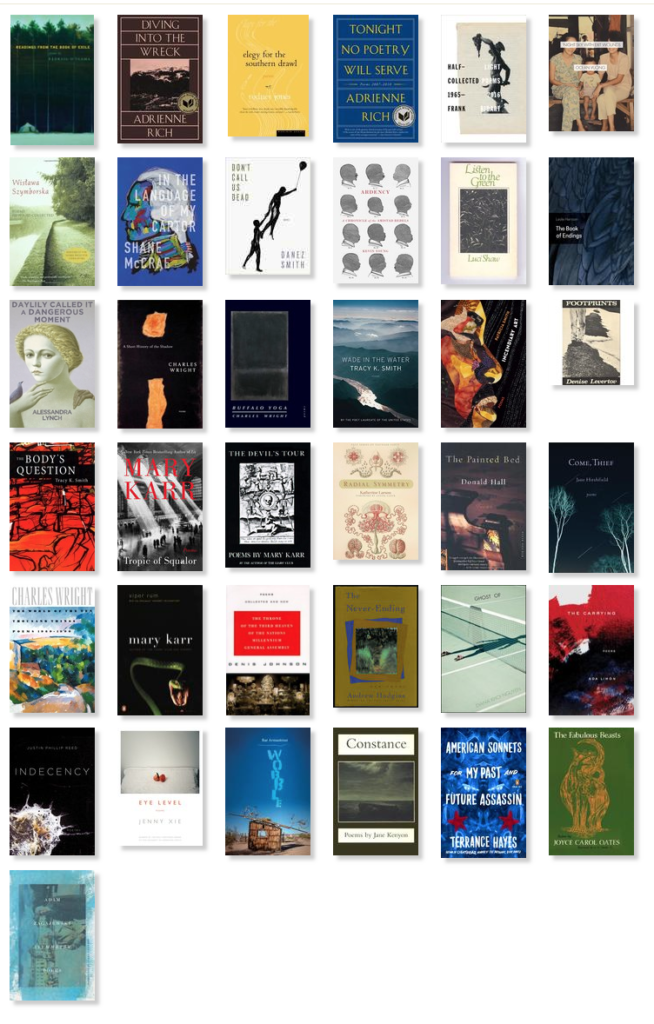

Goodreads tells me I read 37 poetry collections last year, which makes me happy and glad I devoted time to sit with writers who are, to borrow Marilyn Chandler McEntyre’s description of poetry, “paying attention to words at the level of the syllable.” I started off the year rereading a favorite collection from Irish poet Pádraig Ó Tuama, and finished it with a new Adam Zagajewski collection that had just been translated into English from Polish. I read an Adrienne Rich collection Erin had, which led me to pick up another Rich collection when I was at McKay’s Used Books & CD’s, where I find a lot of the older collections I read; that’s also where I found Jones’ Elegy for a Southern Drawl, which I picked up for the title and bought for lines like these: “The boy has heard that music is not sound but an engraving / of silence, / That silence is defined by what precedes and follows it, / and only in this way / Do the moments differ from each other.”

For Christmas, Erin gave me Half-Light, Frank Bidart’s 737-page collected poems that won the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, and I tore through it in a surprisingly short amount of time, loving especially his long poem about Nijinsky (the dancer who choreographed Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring).

I am interested in new poems, poems written by people struggling (and not struggling!) to articulate a response to what they see happening around them, in this second decade of the 21st century. In He Held Radical Light, Christian Wiman writes about his time as editor of Poetry, where as part of his work awarding the Ruth Lilly Prize for lifetime achievement, he made his way “through the collected works of just about every American poet of note.” Before this experience, he had believed that “greatness will out, as it were, that fate will find and save the masterpieces from oblivion no matter what,” but was convinced otherwise by this reading assignment, persuaded of the value of paying attention to what is in front of you. He writes: “There are many, many poems that, though the future will likely find them cold and curiously dark, can nevertheless light the time we’re in. This is a sadness, yes, but also a freedom. Take your eyes off eternity’s horizon and you might miss the meteor that flashes by every century or so (though I doubt it), but the immediate landscape is suddenly much more interesting. There is a spiritual lesson here.”

One of the ways I find new poems that have a good chance of stopping me in my tracks is by paying attention to various poetry awards. I read Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds after it won the T. S. Elliot Prize, and continued my commitment of a couple years to reading at least the 5 books shortlisted for the National Book Award, if not the full long-list. In 2018, that means I read Rae Armantrout’s Wobble; Terrance Hayes’ American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (an amazing collection that included a poem that read differently if you read one line at a time or if you read it as one long run-on sentence, and another that began: “Seven of the ten things I love in the face / Of James Baldwin…); Diana Khoi Nguyen’s Ghost Of (eulogizing a brother lost to suicide, where she reprints family photos with her brother cut out of them, and then on the following page, a poem compressed to the shape of her missing brother); Justin Phillip Reed’s Indecency, and Jenny Xie’s Eye Level, maybe my favorite collection I read all year and also the winner of the Walt Whitman award (“One self prunes violently / at all the others / thinking she’s the gardener.” And from Solitude Study: “Times when I think a mind uncluttered with others / is the only condition for gentleness.”)

Those were from the 2018 shortlist. I started out the year with selections from the 2017 shortlist, including Leslie Harrison’s The Book of Endings, Shane McCrae’s In the Language of My Captors (I heard him give a reading in Grand Rapids where he mentioned how much he loves the stark compositions of Galina Ustvolskaya, and I’ve returned often to them since, an absolutely appropriate soundtrack for 2018), and Danez Smith’s Don’t Call Us Dead (hearing his performance—there’s not a better word—of several of these poem in a classroom at Vanderbilt in the Fall of 2018 made me love them even more).

Reading Charles Wright’s Buffalo Yoga and A Short History of the Shadow prompted me to continue with The World of Ten Thousand Things — Poems 1980-1990, which convinced me to read Wright only in stand-alone books and not collected works. The new collection from our Poet Laureate, Tracy K. Smith’s Wade in the Water, had me digging into her earlier book The Body’s Question, which I bought after hearing her give a reading. Same for Mary Karr—after buying Tropic of Squalor at Parnassus Books the day it came out, I went back and read Viper Rum and The Devil’s Tour. I read Donald Hall’s The Painted Bed after he died, along with Jane Kenyon’s Constance. And the collected poems of Denis Johnson, The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly, after his passing. I wrote at the time that “Johnson’s poems are filled with the same hope and heartbreak and loss and tenacity that animate his short stories and novellas, and I am grateful for all of them.”

The year ended with a preoccupation with Jane Hirshfield’s poetry, particularly “Autumn Quince.” I first came to her work via “Lake and Maple,” which I think I discovered in a collection, perhaps one by Roger Housden — “I want to give myself / utterly / as this maple / that burned and burned / for three days without stinting / and then in two more / dropped off every leaf.” In the years since then, I’ve bought her books whenever I’ve found them at used bookstores and one, her newest, after she gave a reading at Vanderbilt.

Of Gravity & Angels, published in ’88, was the first one I found, and as soon as I read “Autumn Quince” I knew I wanted to someday set it to music. And I finally had the chance. I was asked to write a piece for the Winter concert of the ALIAS Chamber Ensemble here in Nashville, along with a number of other Nashville composers. I settled on what I thought would be the richly warm instrumentation of French horn, English horn, and Clarinet, alongside a string quartet, with the text sung by countertenor Patrick Dailey. The piece is finished now, we have our first rehearsal later this week, and the concert will be on Sunday, the 24th of February, at the Blair School of Music’s Ingram Hall.

Tickets are available here: http://www.aliasmusic.org/novelnoise/.